Urban foraging

Mark Lane at work by the banks of the Exe

Exeter, Devon, 2 May, 2013 -- The arrival of May has all of a sudden brought sunny, bright, warm weather, after what has seemed like more than a year of persistent rain and a winter of biting cold, winds and misery. Today, then, is a day to be outside to enjoy the sun and warmth. So when my friend Mark Lane suggests meeting up to do some foraging, I jump at the chance.

Mark is a fascinating polymath, an expert in many different fields, who, whatever topic he is focussing on, wears his knowledge lightly yet with confident authority. By day, he works for Devon County Council (doing what, I’ve never quite figured out); he is also a wine expert with one of the best, most sensitive and precise palates I have had the privilege to share bottles with. More recently, he has reinvented himself as a wilderness guide, working diligently to acquire a vast repository of knowledge about nature and living naturally in the wild. Mark really can start a fire by rubbing two sticks together, carve a spoon out of a piece of wood, make a shelter to sleep under, or fashion an outdoor privy. And he not only has the knowledge to gather wild edible foods, he has the culinary skill to transform them into delicious meals.

We meet at Devon County Hall. Even before we leave the grounds, Mark is excitedly showing me edible things to eat: a patch of chickweed - “delicious in salads,” he says, pulling off a leaf and munching it. Elsewhere there are some wild green onions growing in the midst of a lawn. And on our way out, we pause by a huge, ancient linden or lime tree, its fresh, bright green leaves just unfurling themselves to the sun. “Lime leaves are fabulous salad vegetable, here, try one.” He picks a tender tree leaf for me to sample, then a half dozen more which he stuffs into a bag. “For tonight’s dinner.”

And so it continues. We cross the Topsham Road and stroll through a housing estate towards the river. When Mark spots a silver birch tree planted in the pavement, goes over and tugs at a bit of papery bark to peel it off. “Excellent kindling to start a fire,” he comments, as he tucks a sheet away in his satchel, “you only need a spark or two on this and it will soon be ablaze.”

We carry along the path towards the old Art College, making our way to the river. But even here along the path, in what is most certainly still an urban environment, Mark keeps pausing as he finds yet more things to taste and eat. There are familiar plants like dandelions - “one of the best salad leaves around, I love the bitter taste and crunch,” he enthuses, handing me a leaf, with the added caveat, “always pick high-growing plants - there is less of a chance that dogs will have peed on them.” Out of a fissure in a stone wall, he finds a clump of wild lamb’s lettuce, tiny leaved, yet with the flavour and soft texture of the cultivated French favourite mâche, only more intense. He pulls up a clump of bittercress; the tiny, round leaves do indeed have something of the pepperiness of watercress - “this makes an excellent soup, just boil it up in some stock, purée it with a handblender, sieve, and spoon in a little double cream” - (here's Mark's bittercress soup recipe).

When we reach the river, Mark bounds down to the water’s edge and pulls up a cattail. Sitting on a log, digging in with his nails, he proceeds to extract all the fluff from the soft, furry, brown reed. “This too makes great kindling to start a fire. Or if it is really cold, you can stuff it down your shirt or trousers to insulate yourself.” Astonishing. Utterly astonishing. Mark really does do things like this (me, I'd be worried about cattail parasites and itching). But that isn’t all: he wades down further into the wetland and pulls up a green plant that had not yet formed its characteristic cattail. Scraping off the river mud, he reveals a pure white root. “This is delicious edible starch that can be boiled up. It tastes rather like jerusalem artichoke. It’s very nourishing and you can actually live off of this,” he explains, wiping off the river mud from his hands on the long grass.

As we stroll along the river, I sample stitchwort (it has a delicate, pea-like flavour), primrose leaves and flowers (the leaves bitter, yet with an intriguing Turkish delight finish), and garlic mustard, with delicate crunchy flowers that taste of wild garlic yet with a flavour that is not persistent.

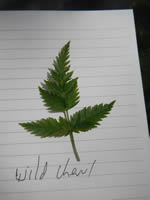

Mark points out alexanders, an umbellifer that had been introduced to Britain by the Romans, something of a cross between parsley and celery, and also wild chervil, with its delicate, frond-like leaves.

“You have to be confident with umbellifers,” he warns. “Look, here’s some hemlock.” To the untrained eye, it appears almost exactly the same as the wild chervil. “Note the mottled stalk, and the pungent, unpleasant smell,” explains Mark. “You would not want to eat this. Just a small mouthful will kill you.” Hemlock was of course the poison that Socrates was compelled to take when found guilty by a jury of his peers for corrupting the youth of Athens. And here it is, growing everywhere - along the path and up stone walls, and mixed within wild beds of delicious edible chervil that I had tasted just minutes earlier.

hemlock wild chervil Mark reminds that many plants are poisonous, such as the lovely foxglove or Digitalis purpurea which can quickly bring on cardiac arrest. “So, as with mushrooms, you do need to know what you are doing,” he warns.

I wonder, when did we collectively lose the common knowledge of this edible larder that is literally all around us, the skill to distinguish the delicious from the deadly? Surely in times of famine, such foods would have been eaten for survival if not enjoyment. And surely there were and must still be crafty country folk who continue to value such wild foods and enjoy them on a regular scale. And what about during and after WWII when there was rationing? Did the population of Britain resort to eating tree leaves and dandelions to liven up an otherwise dull and monotonous diet? Mark thinks not, that knowledge of such foods had already been gradually lost during the centuries of the Agricultural Revolution which saw a move away from subsistence farming, resulting in a surplus of food that paved the way for an exodus to the cities and the eventual rise of the Industrial Revolution. Progress, of course, but along the way a loss of millennia-old knowledge and the traditional skills of the hunter-gatherer that link us to the very origins of our humanity.

These days, Mark and his family eat wild foods most days of the year - or at least at those times when they are readily available. Whether out on Dartmoor, where he spends much of his time, foraging on the coast or estuary, or in the urban heart of Exeter, there is an abundance of wild foods that Mark knows and enjoys.

“Edible plants change with the seasons: in another couple of weeks there will be at least a couple dozen more plants that we could discover. In the autumn, there are all the delicious hedgerow berries as well as any number of mushrooms and funghi. There is a veritable supermarket of fresh veg out there, just waiting to be picked!”

Foraging may be something of a lost art: yet I can assure you, under Mark’s expert tutelage, it is most certainly alive and well in Exeter. If you would like to find out more, visit Mark's Wildnerness Guide web site.

Here’s what we found in a two-hour city centre walk:

chickweed

wild onion

linden leaves

birch

dandelion

lambs lettuce

primrose

greater stitchwort

cattail (greater reedmace)

daisy

herb robert

herb bennett

bittercress

garlic mustard (jack by the hedge)

alexanders

ivy leaved toadflax

hemlock

wild chervil (cow parsley)

burdock

beech leaves

cleavers

navelwort (pennywort)

ground elder

ramsoms (wild garlic)

nipplewort

elder

common mallow

comfrey (knitbone)

hawthorn

tansy

meadowsweet

silverweed

oregon grape (mahonia family)

bay

hog weed

oak gallsBooby's Bay, Cornwall 5 May 2013 -- We escape to Cornwall to enjoy a few days of coastal walking and find that the fields are over-run with alexanders. Heading down the path from Mother Ivy's to Booby's Bay, we wade chest deep through thickets of the flowering umbellifer, the characteristic scent one that Kim remembers from happy childhood summers in this area. With Mark's words of wisdom ringing in my ears (“you have to be confident with umbellifers”) I can't resist picking some for our tea (no sign of hemlock here). Apparently the delicate flowers can be dipped in a light tempura batter and deep fried; the leaves can be added to salad; the stalks can be cooked like celery; and even the seeds can be harvested and used as a herb. We string the stalks and chop them up, boil briefly, then finish in good, unsalted Cornish butter. The thin, tender shoots are sweet, delicately perfumed, delicious, though the thicker stalks are a little too tough and fibrous for our liking. Nonetheless, it is deeply satisfying to enjoy this wild food gathered for free. Though at this moment of the year there may be hundreds or even thousands of acres of alexanders growing wildly throughout Cornwall, all along the the beautiful coastal footpath, on the edges of hedgerow-lined roads, and in whole fields,I would think that there are very few gathering this edible, seasonal treat to eat, which makes the pleasure all the sweeter. “Knowledge,” says Mark, “can give us all the confidence to enjoy a wondrous and delicious wild larder all around us.”

alexanders

![]()

|Home| |QP New Media| |Kim's Gallery|

Copyright © Marc and Kim Millon 1997-2011

![]()